This month our Backyard Gardener Nathan tells of his Appalachian family’s connection to the land, from gardens to coal mines and back again. Stories like this, of families reclaiming old traditions of gardening and getting back to the land, make me proud and grateful of the small role I get to play in their gardening stories.

It was only three generations ago that my family crawled off and out of the ridges and hollows of Wetzel County in the Northern Panhandle of West Virginia.

In the way the ghosts of Appalachia mark time, we may still be there.

My Great Grandpa Ester left sustenance farming and the family’s clapboard house for a steady living in the steel mills being built along the Ohio River two counties up. The steel mills took his arm.

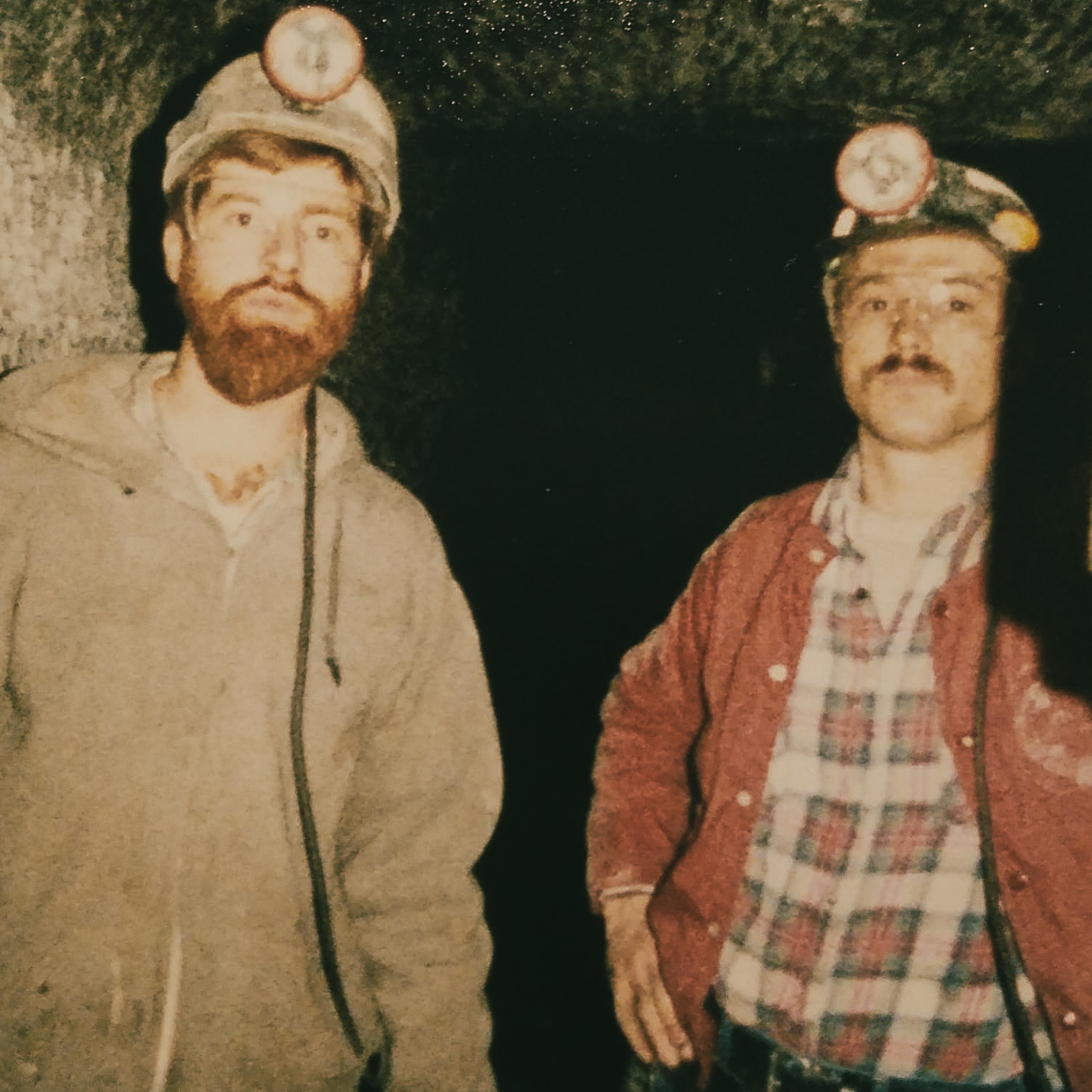

My Grandpa Jack, like so many other West Virginians, found himself diving deep underground in the coal mines that fuel our state and our economy. My dad followed him the week after high school graduation.

My dad made it clear that the coal mines weren’t an option for me. I was going to college.

And with every generation, our family grew bigger and our gardens grew smaller as the memories of our ancestral land became a part of the stories nobody told – too much of our family blood and trauma had been soaked up by that soil.

If you don’t talk about the ghosts, maybe they won’t find you.

But when my dad finally retired, and his days grew longer, a funny thing happened. He decided he was going to put in a garden, a very large garden. He’d spend his mornings and evenings in his sun hat and old tennis shoes shoveling his compost pile and hoeing between rows of tomatoes and corn. After dinner, he’d go to his office and search the internet for the old ways and remember the things he’d forgotten that he’d forgotten.

And he would joyfully give my sister and I fresh vegetables all summer long, “for his Grandbabies,” and my mom would make sure we had plenty of frozen garden corn and canned veggies for the winter.

They had reintroduced the land back into our family.

Over the past few years, my wife and I have had our own journey back to the land, a general reclaiming of our Appalachian heritage. We bought a house in Wheeling, West Virginia, an old Victorian home overlooking the Ohio River that dates back to the early 19th century. Behind that house is a small, rectangular, courtly yard – the kind made to entertain guests of a certain station and of a certain era.

We are not of that station. We are not of that era.

We are people of the hills and hollows.

And so, this year, we are putting in a garden. It’s not huge, just 650 square feet or so, but it’s land that we will pour the memories and challenges that our own family experiences, the pushings and pullings of a blended family that includes six children and complex relationships, but who long to be reconnected to the land that we pushed away so long ago.

We will pour ourselves into the soil and let it filter our pains and joys into something that nourishes our bodies and our souls.

It’s our dirt, and we’re returning to it – not as a lawn of status, but as a land that feeds us.

We will nurture it, and we’re praying it will return the favor.

And somewhere along the way, we hope our ghosts will find their peace.

Beautifully written Nathan. I love the included photos.

Thank you for sharing your story, Nathan. I’m glad you’re able to reclaim this piece of your family’s history.