Hi, this is Karline Jensen with High Rocks. Pete and Leah and I are attending the West Virginia Better Process Control School for Acidified Foods Safety at the Small Farms Conference in Charleston, WV today and tomorrow. This training is being taught by Professor Joe Marcy from Virginia Tech, and if we pass all nine tests we have to take over the course of the two days of instruction, we will each get a lifetime certificate that is necessary for the production of Low-Acid and Acidified Foods for sale in West Virginia.

So far we have learned about the Microbiology of Thermally Processed Foods, the regulations for Acidified Foods production (http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=114&showFR=1), guidelines for Thermal Processes, Food Container Handling, and Instruments and Equipment. Tomorrow we will cover Principles of Food Plant Sanitation, Records for Product Protection, Closures for Glass Containers, and Flexible and Semi-Rigid Containers.

The professor is fun and really covers what we need to know to pass the tests; so far everyone in the class has passed every one. He has also given out a lot of prizes designed to reduce our test anxiety. I received a battery powered bubble maker. Leah received a teddy bear. They also put out chocolate candy in front of us and we all have to admit that the sugar has helped us to pay attention.

Basic home canning guidelines are designed to make it easy for everyone to preserve their harvest in a way that will keep their families safe from pathogens that cause human illness. This class explains the microbiological science that makes this possible. The bacterium Clostridium botulinum produces the most deadly toxin known to man when its vegetative cells reproduce. C. botulinum is found naturally in the soil and water we use to produce our food. It grows best at 86 to 98 degrees F. Under colder, more adverse conditions it will turn into a spore, which is its dormant stage. These spores are very difficult to kill with heat; they can survive in boiling water for over 16 hours; but they can be kept dormant in a state where they don’t produce toxins, by lowering the acidity below 4.6.

Thermal processing is not designed to kill thermophilic bacteria, the ones that grow best at 122 to 150 degrees F. These bacteria do not cause illness in humans, but many of them do cause spoilage. The professor told an interesting story about food that was sent to Kuwait and was not kept under standard storage conditions. The heat of the desert caused all of the food to spoil, even though it would have kept fine under normal conditions. Another interesting story was of a can of peppers that exploded. Apparently momentary failure of the seal had allowed cooling water to enter. The can subsequently sealed up tight, but over time the bacteria produced enough gas to swell both ends of the can, and when the pressure finally forced an opening in the seal, it ended up causing the can to spin in circles, spewing its contents around the entire room.

We learned that the easiest way to make bleach ineffective is to use more than directed. The amount of chlorine you need depends on the levels of inorganic chemicals such as Mg, Ca and Na, as well as organic chemicals such as proteins, fats and carbohydrates. Basically the chlorine has to react with all these other chemicals before it is available to kill bacteria. You can measure how much chlorine is free for germicidal activity with paper test strips. The reason too much bleach does not work is that it raises the pH of the water, and bacteria are much more difficult to kill in a less acid environment. If you can smell the chlorine, you are probably using too much. A solution might take 8 minutes to kill the bacteria at a pH of 6.0, but if you raise the pH to 8.0 by adding too much bleach, it will actually take 42 minutes to kill the same amount of bacteria.

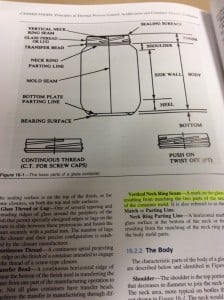

All glass was made by hand before the invention of automatic machine production in 1903. The stippling that you see on the bottom of glass jars is to help keep them from breaking, since any scratch in the surface might be a score line that the glass could easily break along. The history and principles that we have learned in this class are quite interesting, and the professor has kept the focus on the types of processes that the small WV producers in the room said they were working on developing. We want to produce salsa, pickles and other products from the produce that our gardeners are growing. Teresa Halloran with the WV Department of Agriculture helped organize this class, and she says the next step is to make a batch of salsa, send her a couple jars and the recipe, and she’ll help us figure out everything we need to do to make it legal for sale on the shelves of our local stores. We’re all set to start adding value!

Hats Off to you both for this undertaking. If you can write about it in this blog, you must be mastering it.

Sounds Great! Good job all of you! Bleach info fascinating.

I have seen people just pour a few glugs of bleach into their sanitizing water, and I always thought, they should read the label and measure! Now I can explain to them why this is important.

This is very useful information, Karline! Thank you for sharing!

I wish logan could be notified or have some of these workshops

You could call Teresa and ask her where the next training will be held, her number is 304-558-2210, Ext. 2590. She is the one that organized the training in Charleston. Also call your extension agent, (304) 792-8690, and ask them to put you on their list to notify for all the workshops they offer in your county. Our agent is doing one on apple tree pruning this week.